Friday, June 29, 2012

A Line No Man Should Cross

There's a line that men like us have to cross, says Captain Martin Walker after we are bombarded with images of him shooting, stabbing, and murdering people amidst the explosions of warfare (and, seriously, is that the voice of Michael Douglas?). This is the trailer for the new third-person shooter video game Spec Ops: The Line, which comes out today (June 29).

While I am not a fan of violent video games to begin with, especially those of the Military Entertainment Complex, the slogan for this new game has me totally disgusted. Captain Walker's catchy phrase upsets me for a couple of reasons. First, it is an imperative: men like us have to cross the line. It gives the impression that this kind of violence is an unavoidable fact of reality. There is no other choice, someone must cross the line. Is this not the great lie of militarism? It is this rhetoric of the imperative that teaches us that violence is the only solution and we have no choice but to cross the line. Second, it smacks of an elitist machismo that depicts war and murder as something only the strongest men can do. The slogan shrewdly provokes adolescent male audiences to prove their manhood by crossing that obscure line that is war.

I recently learned just how obscure this line can be. A few weeks ago one of my father's friends, who is in the Army Reserves, was in California leading a squadron through a virtually simulated training session. After an intense firefight with enemy soldiers he and his unit learned that they failed the training session. They failed because he, being the commander, had told his unit not to shoot a 12-year-old boy who had picked up an I.E.D.

Is this the line that some men have to cross? Is this the line that only certain men are strong enough, brave enough, patriotic enough to cross? Is this the line that must be crossed to maintain life as we know it?

Forgive me for being dramatic. I don't mean to take one example and extrapolate it into a polemic. It's just that I am tired of militarism's lies. I'm tired of video games and TV news that tells us that war and violence is OK - because we don't have to see real blood, hear real screams, or smell real dead bodies. We get a nice, clean war (thank you Hollywood), not a real, bloody war. We get Captain Walker and the Spec Ops, not a war in which grown men are forced to shoot young boys holding explosives. We're told that there's a line that some men have to cross. No. I'm sorry. That's a line no man should cross.

And isn't this the tragedy of war? It creates total lose-lose situations by forcing human beings to cross lines they were never meant to cross. The soldier who shoots and kills another man doesn't win. She or he loses as well. Anyone who's read Anthony Swofford, seen Jarhead or read about PTSD knows this.

As you can see, I'm not explicitly writing to gamers or calling for the wholesale renunciation of video games (not even this one). But I am saying that this new Spec Ops game is yet another pawn in militarism's game of control. And if we choose to passively accept the ideas of the Captain Walkers of the world, there is no hope for a time when we "learn war no more," (Isa. 2:4, Micah 4:3). As long as we believe that war's horrific lines must be crossed, there is no hope for the Reign of God. But perhaps there's a line that followers of Jesus have to cross. Maybe that's the line across which we move from the way of militarism to the way of Christ: love for enemies, proactive peacemaking, and non-violence. If you ask me, crossing this line is probably the most "violent" thing a person can do.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

10 Songs You Know You Know (But Might Not Know)

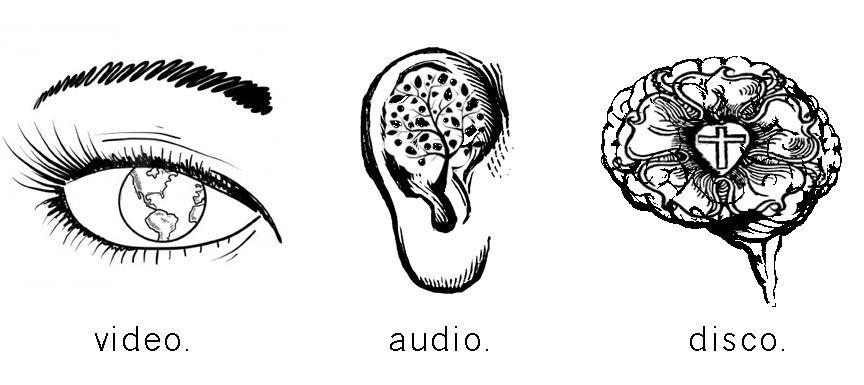

Here's something you should know: ALL ART IS A COPY OF OTHER ART. No, really. There's even a website devoted to this phenomenon, it's called Everything Is a Remix. (My favorite video is one in which they show all of the copied martial arts moves in The Matrix.) Some even say that there are only three ways to create art: copy, transform, combine (see photo left). One of the best examples of this is sampling in music. Here are 10 examples.*

10. Everybody knows Beyonce's "Crazy in Love" because it topped the charts and it was in a 2003 Pepsi commercial. But you might not know that the music sample comes from The Chi-Lites "Are You My Woman? (Tell Me So).

9. In 1981 a group named Wild Sugar put out a song called "Bring It Here." Can you guess where this reappeared 5 years later? Hint: a group of boys made a song about a metal primate. (Answer)

8. Touching the sky certainly requires upward movement, which is probably why Kanye West's "Touch the Sky" utilizes a sample from Curtis Mayfield's 1970 hit "Move on Up."

7. Listen to the first 5 seconds of Experience Unlimited's "Knock Him Out Sugar Ray" and see if you can guess where this drum sample later reappeared. Hint: "That was a good drum break..." (Answer)

6. M.I.A.'s "Paper Planes" was one of the biggest chart toppers of the last 5 years. But do you know where her guitar sample comes from? It's blatantly "borrowed" from The Clash's "Straight to Hell."

5. One could devote a whole website to Jay-Z's samples but one of my all time favorites comes from "December 4th" off the Black Album. This catchy sample comes from The Chi-Lite's "That's How Long."

4. Miss Rhianna is a queen of sampling. Her 2006 hit "SOS" clearly sampled Soft Cell's "Tainted Love." And her "Talk That Talk" gets its guitar hook from "Intro" by The Xx.

3. There ain't no pop music like Motown. That's why Justin Bieber (a.ka. his producers) pretty much stole the Temptation's song "Lady Soul" to recreate his hit "Baby."

2. If you think that Hip-Hop and R&B are the only genres that borrow from other tunes, think again. It's kind of creepy to hear how closely Albert Hammond's "The Air That I Breathe" sounds like Radiohead's 1992 hit "Creep." See also Radiohead's copy of The Beatles on Karma Police.

1. Think that catchy melody in Coldplay's "Viva La Vida" was all Chris Martin? It may have been. Or it may have been the sweet guitar riffage of Joe Satriani...

* Another great example is this blog post. Most of this content is not my original thought or work. I have simply connected the dots (combine) and re-presented the information in a new medium (transform). If you want to check out more music samples, go to WhoSampled.com

10. Everybody knows Beyonce's "Crazy in Love" because it topped the charts and it was in a 2003 Pepsi commercial. But you might not know that the music sample comes from The Chi-Lites "Are You My Woman? (Tell Me So).

9. In 1981 a group named Wild Sugar put out a song called "Bring It Here." Can you guess where this reappeared 5 years later? Hint: a group of boys made a song about a metal primate. (Answer)

8. Touching the sky certainly requires upward movement, which is probably why Kanye West's "Touch the Sky" utilizes a sample from Curtis Mayfield's 1970 hit "Move on Up."

7. Listen to the first 5 seconds of Experience Unlimited's "Knock Him Out Sugar Ray" and see if you can guess where this drum sample later reappeared. Hint: "That was a good drum break..." (Answer)

6. M.I.A.'s "Paper Planes" was one of the biggest chart toppers of the last 5 years. But do you know where her guitar sample comes from? It's blatantly "borrowed" from The Clash's "Straight to Hell."

5. One could devote a whole website to Jay-Z's samples but one of my all time favorites comes from "December 4th" off the Black Album. This catchy sample comes from The Chi-Lite's "That's How Long."

4. Miss Rhianna is a queen of sampling. Her 2006 hit "SOS" clearly sampled Soft Cell's "Tainted Love." And her "Talk That Talk" gets its guitar hook from "Intro" by The Xx.

3. There ain't no pop music like Motown. That's why Justin Bieber (a.ka. his producers) pretty much stole the Temptation's song "Lady Soul" to recreate his hit "Baby."

2. If you think that Hip-Hop and R&B are the only genres that borrow from other tunes, think again. It's kind of creepy to hear how closely Albert Hammond's "The Air That I Breathe" sounds like Radiohead's 1992 hit "Creep." See also Radiohead's copy of The Beatles on Karma Police.

1. Think that catchy melody in Coldplay's "Viva La Vida" was all Chris Martin? It may have been. Or it may have been the sweet guitar riffage of Joe Satriani...

* Another great example is this blog post. Most of this content is not my original thought or work. I have simply connected the dots (combine) and re-presented the information in a new medium (transform). If you want to check out more music samples, go to WhoSampled.com

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Why Worship

I was reading over on my friend's blog about James K.A. Smith's book Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview and Cultural Formation and I was reminded of Anne Lamott's retelling of the story of A.J. Muste during the Vietnam War. The story goes like this:

I was reading over on my friend's blog about James K.A. Smith's book Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview and Cultural Formation and I was reminded of Anne Lamott's retelling of the story of A.J. Muste during the Vietnam War. The story goes like this:Abraham Johannes Muste (1885-1967) was an American clergyman and political activist. During the Vietnam War he stood outside in front of the White House every night with a lighted candle. He stood in silent protest night after night no matter the weather, no matter the turn out of activists. He stood with others and he stood alone. Finally, one evening a reporter approached him and asked, "Mr. Muste, do you really think you're going to change the policies of this country by standing outside with a candle?"

And that is why I worship the God revealed in Jesus.

--> Read Joe's review of Desiring the Kingdom

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

The Terror of Love

With my wedding less than 6 weeks away I am excitedly working on writing vows for my beloved. Part of my preparation for this involved reviewing materials from a course I took in seminary called Theology of Romantic Love. As I re-read an exegesis of Song of Songs 5:2-6:3, I was reminded that romantic love is a fearful thing. Its intimacy requires a vulnerability that is psychologically terrifying. Yet at the same time this vulnerability is the very means to a divine-like intimacy that is characterized by the Song of Songs' mantra: I am my beloved's and my beloved's is mine. Here is some of that exegesis (if you're not up for the read, skip down to "Interpretation").

Literary Context

The

pericope at hand is sectioned off fairly clearly by 5:1 and 6:4. The preceding poem (4:9-5:1) comes to a

definite conclusion by describing the man’s entrance into the woman’s “locked

garden” (4:12) and his subsequent enjoyment (5:1). 5:2 then begins a new scene. Just so, 6:4 begins a new poem and thereby marks the end of

our pericope at 6:3.

More

interesting, however, is that 5:2-6:3 closely resembles another poem, perhaps

even two. The obvious parallel is

found in 3:1-5 where, beginning on her bed at night, the woman ventures out to

the city to search for her lost lover until she finds him. The poem recounts

almost identical events (encountering the watchmen and adjuring the daughters)

and seems to express a similar focus on the yearning of desire.

A

weaker but nonetheless present parallel may be found in 2:8-17. The resemblance stems from the poem’s

description of the man coming to the woman and calling for her (cf. 5:2). Despite

these similarities, 5:2-6:3 is certainly a unique poem with nothing in the book

quite like it. It is beautiful and

dark at the same time. As I shall expound below, I believe that it attempts to

capture the ineffable paradox of intimacy (viz. sexual intercourse).

Detailed Exegesis

For

the sake of space I will not examine each verse in detail but will devote most

attention to the key elements of the poem, namely verses 1-8 and 6:1-3. Also

worth noting is that I am not concerned with any sort of logical explanation of

this poem – for it is a poem! I will make no attempt to justify the sequence of

events in the poem’s scenes.

Instead, my aim is to understand the feelings, ideas, and convictions

expressed in the poem.

5:2 – The woman’s voice opens the poem by recounting a

past occurrence (hence, I will tend to describe the poem in the past

tense because I think something is lost if translated to present tense). The woman tells that she slept yet

lightly enough to hear the knock on the door and the call of the man. Was she dreaming? Is the whole poem a

dream or just a part of it?

Commentators seem to differ on this[1]

but it is not central to my interpretation since I aim to consider the

psychological meaning of the images.

The

man’s request was for intimacy with the woman (i.e. sexual intercourse). This is inferred by the double meaning

of the man’s request (“Open to me”) and the implicit but unmentioned door, which,

according to Longman is symbolic of entry into the woman’s body.[2] That the man was dripping with dew from

the night may imply further sexual innuendo but need not necessarily. What is

clear is that the man had come with desire

for his “perfect one.”

5:3 – It is unclear who is speaking. Is it the man or the

woman? Garrett interprets this as

the man’s entreaty, but he is in the minority view.[3] If it is the woman, it is unclear

whether or not she speaks to the man, to herself (as soliloquy) or perhaps to

the daughters of Jerusalem found in v.8.[4] Nevertheless, the woman’s twofold

lament is clear: she was unready for the man. That she was stripped and bathed suggests that she was

prepared for sleep and not for sex.

I believe that this verse is best read as disclosing details of the

scene rather than dialogue between the lovers. Moreover, the lines express the woman’s feeling of surprise,

vulnerability, and perhaps even reluctance.

5:4 – The poem’s excitement increases as the woman

describes how the man touched his “hand to the latch,” (RSV). Longman translates this more intensely

as “hand through the hole” and argues that this language is undoubtedly sexual.[5] I find this convincing since the

following line describes the woman’s reaction: “my heart was thrilled within

me,” (RSV). Here the Hebrew me’ah

(translated “heart”) is more rightly conveying a deeper, more private, area of

the body.[6] When combined with the word hmh (translated “thrilled”), I believe it is clear that

the act of the man – whatever it details – caused sexual pleasure for the woman

(and probably the man as well).

These intense images portray pleasure.

5:5 – The pleasure described in 5:4 is enough to have

roused the woman to open to her beloved.

The woman explains that she moved to the door and her hands “dripped

with myrrh,” (cf. 1:13; 3:6; 4:6; 5:1).

The myrrh does not indicate anything specific but simply adds to the

intensity of the sensual pleasure.

5:6 – In a kind of anticlimax, the woman describes the

poem’s unpredictable twist: she opened to her beloved only to find him

absent. Indeed, it is even more

anticlimactic for the reader since we are given no explicit reason for the

man’s exit. The woman alludes to

her previous reluctance in v. 3 and comments, “My soul failed me when he

spoke,” (RSV). The NIV translates

this comment as “My heart had gone out to him when he spoke.” Both translations suggest that the

reason for the man’s departure was the woman’s reluctance to answer his initial

call, but, as I have noted, any attempt to make logical sense of this scene is

futile. Rather, I believe that

this central stanza of the poem expresses the instantaneous vulnerability

of intimacy (more below). Garrett offers an interesting and very plausible

interpretation that the man’s absence is nothing more than his orgasm.[7] The verse ends with the woman’s

description of her failed attempts to “find” her beloved.

5:7 – The woman now tells a traumatic scene in the city:

the “watchmen” find her and beat her. As in previous passages,[8]

the “city” (contrasted with the country) represents a difficult “place” to be

and express love. What is significant here is not what the watchmen, city, or

physical beating literally represent, but rather the feelings that they convey.[9] The images clearly express fear and

anxiety.

5:8 – The woman here speaks directly to another (her

audience?). She adjures the

“daughters of Jerusalem” to tell her beloved (should they find him) that she is

“sick with love.” Such an intense

description of the woman’s experience seems to convey the way that love and

desire consumes the human psyche.

5:9 – The daughters of Jerusalem fail to recognize the

uniqueness of the man: “What is your beloved more than another beloved?”

(RSV) The daughters’ response

expresses the distance of those outside the lovers’ intimacy

(i.e. those on the “outside” cannot understand). This scene also sets up the

woman’s wasf in 5:10-16.

5:10-16 – This is the woman’s first and only wasf

in the entire book. As such it is

especially fitting for this poem because the context emphasizes the uniqueness

of personal experience. Who can

describe the man? Only the woman who has been intimate with him. There is not room to add commentary on

the images of the wasf.[10]

6:1 – Again the daughters of Jerusalem inquire to the woman. This time, however, they do not ask a

“what” question but a “where.” It

seems that the woman’s wasf was sufficient to capture their

attention and they too now desire to know where this exceptional man may be

found.

6:2,3 – The woman answers with an unexpected response. Though previously she was “sick with

love” and could not find her beloved, she now claims to know exactly where he

is: “My beloved has gone down to his garden, to the beds of spices, to pasture

his flock in the gardens, and to gather lilies. I am my beloved’s and my

beloved is mine; he pastures his flock among the lilies,” (RSV). That the man

is in “his garden” brings to mind the explicit image of the woman’s body in the

foregoing poem (4:19-5:1). Further

support is found in the woman’s clear explanation that the man is not missing

but is, in fact, intimately joined to her: “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is

mine.” The

man is not lost (and never was).

Instead, the woman explains that she and she alone knows where the man

described in the wasf is to be found: in

the intimacies of sexual intercourse.

Interpretation

As

Garrett rightly notes, “All of this makes for narrative chaos if read in any

literal way.”[11] The

illogical drama of the poem does not recount literal events but is rather a

poetic expression of the psychological experience between lovers. More specifically, I believe that the

poem expresses the paradoxical feelings of intimacy vis-à-vis sexual intercourse.

As such, the poem captures the depth of love as not only a physical act, but

also a psychological phenomenon.

The

poem conveys three waves of emotion: 5:2-6; 5:6-9; 5:10-6:3. The first wave expresses the lovers’

desire for one another. The

imagery is obvious and the couple takes pleasure in consummating their

love. The woman’s reluctance in v.

3 ought not be viewed as literal disinterest in her lover but rather an

expression of the vulnerability that a (possibly virgin) wife might feel during

the moments of sexual consummation.

Again, the poem captures the storm of emotions that are part of sexual

intimacy. Any feeling of

reluctance is quickly replaced by passion and desire in verses 4-6. The physical pleasure is not

disconnected from the psychological; it is all connected.

The

second wave of emotion in 5:6-9 conveys the woman’s fear and anxiety. Anyone who has ever been in an intimate

sexual encounter understands that with the passion and pleasure of sex come the

fears of exposure (cf. Gen. 3:7).

The disappearance of the man in v. 6 expresses the deepest of human

fears: opening to our beloved and being rejected. The subsequent verses

continue to portray the woman’s fear of losing the one with whom she has been

most intimate. Such is the power

in sexual intimacy and it plays upon our psyche. Indeed, it makes the woman

sick. Hence the repetitious warning: Do not awaken love!

The

woman’s fears are ultimately squelched in the third wave as she remembers the

nearness of her beloved. The man

is not aloof as her fears might imagine; he is actually so near that he belongs

to her and she to him. This reassurance is something that only she can know

because she alone has known him intimately. Thus, the woman offers her unique description of the man in

vv.10-16. Her wasf is the location of

her reassurance. It is as if the wasf grounds the woman in her unique view of the man and reminds her of

their intimacy. Then she is able

to “find” him: Aha! He is here with me in my garden.

I

have noted throughout that I believe this poem expresses the paradoxical

emotions of intimacy vis-à-vis sexual intercourse. Provan agrees in his

assessment: “Love, when stirred up, will involve wonderful moments of intimacy

and passion. It will also involve

moments, however, of vulnerability, insecurity, fear, and loss.”[12] The truth of this poem is not that

lovers experience such psychological paradox, though it is true. The deeper truth, I believe, is found

in the concluding line of the poem: “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is

mine.” Despite the [sometimes

illogical] drama of love, the two lovers belong to one another.

Theological Interpretation

Just

as human love is characterized by paradox, so too is divine-human love. I would like to posit that the picture

of human love painted in this poem is an image of the divine-human

relationship. As such, the love that characterizes the divine-human

relationship is not agape, but eros.[13] This love is characterized by

passionate desire for one another.

However,

just as the lovers of the poem experience psychological fear and vulnerability,

so too do human beings – and, I would argue, God as well. Human beings

undoubtedly experience fears and vulnerability when we become intimately in

love with God (e.g. Psalms 13 and 22; the Dark Night of the Soul, etc.). I also believe that, through Jesus,[14]

God knows this paradox as well; for is there a more intimate moment of love

between humans and God than the Cross? (c.f. “I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved

is mine”) Paradoxically, is there

a moment when the lovers are not seemingly

more aloof? Indeed, the

psychological paradox of intimacy portrayed in the lovers of the Song is an

image of the intimacy between our Divine Lover and the human Jesus.

Application

Intimate

love is risky business. To apply a

quote from Richard Bauckham, intimate love demands what it offers and offers

what it demands.[15] Intimate love demands the risk of

exposure and vulnerability, but at the same time it offers the reward of

supreme love and belonging.

After

reflecting upon this poem, it seems to me that the wasf has a key role to play in the process of intimate

love. More specifically, perhaps

the wasf is a crucial means for

overcoming fear and finding reassurance.

As I noted above, the woman seems to find reassurance after describing

her beloved. Perhaps we too might

apply this strategy when fears overtake us. There is a profound wooing that occurs when we describe our human lover for who

they are. In my own experience,

the act of poetically describing my beloved helps me to see her as unique and

reminds me why I love her so.

The

same may be true for describing the eternal and invisible God. As Jensen notes, “Christ on the

cross…is a figure naked to the world; the church points up to him and says, My

lover is like that.”[16] In the midst of our deepest fears that

the One who knows us most intimately might reject us, perhaps the wasf is a tool for overcoming fear and returning to our

Lover’s Garden (cf. Gen.2:8).

A Jesus Wasf

My Beloved is the finest lover of all;

A million blazing suns could not outshine Him.

Like the whir of a warm spring rain,

His voice soothes my heart.

His hands are camel’s hair;

And His eyes like doves.

His skin is like sea glass,

Broken and bruised by waves.

His garments of purple are finer than diamonds;

The rarest of stones envy him.

His lips drip with sweet honey,

From His tongue comes heaven’s manna.

His blood is the essence of life,

His veins are the rivers of being.

He alone is my lover,

My beloved is my friend

and God.

[1]

Mitchell believes 5:2-5 to be dream, 878. Provan views 5:2-7 as dream,

341. Longman III remains ambiguous

and does not deem the matter significant, 165.

[2]

Longman III, 166.

[3]

Duane Garrett, World Biblical Commentary: Song of Songs, vol. 23B (Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson,

2004), 208.

[4]

Jensen, 53.

[5]

Longman III, 162, 167.

[6]

Longman, III 167.

[7]

Garrett, 212.

[8]

e.g. 1:5-6; 3:2-3

[9]

Even Longman III treats this scene as dream rather than literal event, 169.

[10]

For details see Garrett 202-224; Mitchell 918-944.

[11]

Garrett, 224.

[12]

Provan, 341.

[13]

Jensen, 17.

[14]

I might argue that God also knows through the Spirit with Jesus and all human

beings; but in Jesus in a unique way.

[15]

Trevor Hart, “Imagination for the Kingdom of God?” in Richard Bauckham, God

Will Be All in All: The Eschatology of Jurgen Moltmann, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001), 71.

[16]

Jensen, 58.

Monday, June 25, 2012

If Jesus Reveals God...

Call me crazy, but I've come to believe that the scandalous opinion of Christian theology is that the person Jesus of Nazareth reveals God. John the Evangelist wrote, "No one has ever seen God; the only Son has made him known." (John 1:18) The Apostle Paul once said that in Jesus "the fullness of God was pleased to dwell." (Col. 1:19 and 2:9) The author of Hebrews also confessed that Jesus "reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of God's nature." (Heb. 1:3)

Others have come to believe this as well. The second century Christian bishop Irenaeus once said that the Incarnation of Jesus "means nothing else than that God is comprehended in Christ alone." Constructive theologian Sallie McFague calls Jesus the parable of God. She asserts that Jesus is the metaphor for understanding the character and nature of God. We cannot go around Jesus nor contemplate God apart from Jesus of Nazareth. Another theologian, Jurgen Moltmann writes, "When the crucified Jesus is called the 'image of the invisible God,' [Col. 1:15] the meaning is that this is God, and God is like this."

Much of the time Jesus is viewed as God's special rescue mission and is seen more in terms of what he does [for us] rather than who he is. But the Christian tradition pushes us to see Jesus more in terms of him "who reflects God's glory" and "makes God known." In this sense, Jesus is the normative paradigm for thinking about God. He is like the special lenses we must put on when attempting to look at God, for without them we cannot see God.

According to Christianity's outrageous faith claim, the only way to know God is through Jesus. What does this mean for our view of God?

According to Christianity's outrageous faith claim, the only way to know God is through Jesus. What does this mean for our view of God?

If Jesus reveals God, then...

- God is not a coercive being

- the power of God is revealed in weakness

- God is a God of kenosis (i.e. gives up power for the sake of others)

- God speaks and moves within the limitations of particular cultural contexts (i.e. within the language, thought patterns, symbols, etc.)

- God speaks through stories, not just propositions and 'facts'

- God is fundamentally concerned for the poor and the oppressed (Luke 4:18-20); yet also the oppressors (Matt. 9:9-13)

- God suffers (indeed suffered a most shameful and grievous death)

- God bears the scars of suffering

- God would rather experience death than be without creation

- God is not repulsed by sin but chooses to be the friend of sinners

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

The Anti-Beatitudes

Sometimes it helps to think about what things are not in order to understand what they are. This has sometimes been called the via negative, the way of the negative (or the "apophatic" tradition). In this case I have turned the beatitudes of Jesus into paraphrases of their opposite expression. They are by no means an exact inversion, but rather an interpretation. Nevertheless, the process of thinking about what words might articulate the opposite of what Jesus taught in the Beatitudes is a fascinating way to explore His teaching further.

Particularly compelling is that these "Anti-Beatitudes" resonate with me in many ways that Jesus' Beatitudes do not. In other words, I find many of these phrases more descriptive of my lifestyle than those found in Matthew's and Luke's gospels. Perhaps you too will find this a meaningful reflection.

-jmw

- Blessed are the rich, for they will struggle to enter the kingdom of God. (cf. Luke 6:20, 18:24-25)

- Blessed are those who party all the time, for they need nor receive comforting. (cf. Matt. 5:4)

- Blessed are the powerful, for they shall take hold of the earth. (cf. Matt 5:5)

- Blessed are those who crave unfairness, for their craving shall be insatiable. (cf. Matt. 5:6)

- Blessed are the merciless, for they will obtain no mercy themselves. (cf. Matt. 5:7)

- Blessed are those with dishonest hearts, for they cannot see God. (cf. Matt. 5:8)

- Blessed are the war-makers, for they shall be called the enemies of God. (cf. Matt. 5:9)

- Blessed are those who are rewarded for injustice, for they will not receive the kingdom of God. (cf. Matt. 5:10)

- Blessed are you when people praise and reward you for rejecting Jesus, the Christ. (Matt. 5:11)

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

4 Views of Biblical Inspiration (by Donald J. Brash Ph.D.)

General Inspiration

"Arrow number 1 represents the belief that the Bible is inspired in the way that, let's say, Shakespeare was inspired. I call this the 'general inspiration' of Scripture. According to this view the Bible is fully a human work; God did not inspire it in any direct sense. The biblical writers wrote when 'the muse' (Greek deities of artistic inspiration), rather than the Holy Spirit, 'was upon them.'

In this view, the Bible should be approached like any other book that has had culture-shaping influence. After all, the Bible has numerous characteristics in common with other books or ancient texts. It contains inconsistencies and apparent contradictions, and there are variants among the manuscripts. Readers who take this view of inspiration are likely to employ an inductive, to be distinguished from a deductive, method of assessing the evidence from the Bible about the Bible.

For example, a reader discovers that there are differences among the Gospels. The wording and the ordering of the stories they have in common are sometimes inconsistent. The Gospel of John, for instance, places the cleansing of the temple on the day of Christ's triumphant entry into Jerusalem at the beginning of Christ's ministry. The other Gospels place it much later. In acknowledging this, the reader's understanding of biblical inspiration begins to change. It is becoming more inductive; that is, he or she begins to look at what is in the text and then draws conclusions about the Bible based on what is there. A deductive approach might reason that, since the Bible is accurate in every detail, the contradictions are in the way a reader interprets them. Readers might then put a great deal of effort into resolving 'apparent contradictions.'

Many differences of detail such as these appear in the Bible. These, along with other textual problems, are cited as justification for the general inspiration point of view about the very human nature of the Bible. Humans, however, are not capable of a purely inductive or a purely deductive approach to learning. Those who begin 'from below' also bring assumptions to the process of interpretation, and an approach that leans toward the inductive does not necessarily render one's view of the Bible 'low.' "

Varied Inspiration

"According to 'varied inspiration,' number 2 on our diagram, some passages are included in the Bible by God's will. Others are not. Inspiration is like an uneven landscape. Even where the inspired parts of Scripture are concerned, some passages are inspired differently than others, and for different purposes. This is reflected in the liturgical invitation to 'listen for,' instead of 'listen to' the Word of God.

The distinction between aspects that are and are not inspired by God can sometimes be arbitrary from the varied inspiration perspective. That is not to say that readers who take this view are not thoughtful and discerning. Discussing the issue, one of my students, for example, pointed out 'that certain parts of the Bible are more or less related to Christ, and, hence [more or less immediately instructive], for Christians.' In my opinion, the entire Bible is intended by God for our instruction, but inspiration correlates with genre and discernible intention, and to determine this sometimes requires vigorous wrestling with the texts in their contexts."

Verbal Plenary

"Arrow number 4 points downward. The belief that God guided every word of the writers of Scripture is frequently referred to as 'verbal plenarism.' You know the word verbal: It comes from the Latin verbum, meaning 'word.' The root of the word plenary is the Latin plene, which means full. In this view, God not only inspired the writers, God fully inspired them. In the strictest verbal plenary view, every word is God's Word, and every jot, tittle, and dash in Scripture is meant by God to be there.

The perspective of verbal plenary inspiration is justified by the belief that the Bible attests to its own inspiration. It is in this sense self-authenticating. The key texts that testify to this conclusion, among others, are the ones we considered in the previous chapter: 2 Timothy 3:16, 2 Peter 1:20-21, and John 10:35. In the latter verse, the way Jesus treated the Hebrew Scriptures is the focal point. In this approach the Bible is interpreted deductively, which is to say the interpreter adheres to a theology of the Bible into which the facts must be fit. Gleason Archer, quoted earlier, approached the Bible from this kind of perspective. Paul Achtemeier did not.

When they encounter problems with the text, interpreters from the verbal plenary perspective are forced to try to reconcile differences. In the end they are forced to acknowledge that their belief in the verbal and historical inerrancy of Scripture is based on assumptions about the so-called 'autographs' - the original biblical texts. None of these are extant, so there is great effort to reconstruct them. This process raises yet other questions. Multiple authors and editors created some books of the Bible. At which point in that long process did the text become inerrant? We are left with the texts we have in hand; it is their status that is most relevant to us here and now."

Incarnational

"As I said early on in this book, I prefer the 'incarnational' view of biblical inspiration (number 3 on the diagram). According to this view, the Bible is to be understood as incarnational in a way that is analogous to the Incarnation of the Word in Jesus the Christ. There is a connection between Christ the Word and the Scriptures: Christ is the Word to which the Scriptures as a whole bear witness (though not in every detail), and through the Holy Spirit Christ the Word uses the Scripture to bear witness to God.

The incarnational view of the Bible affirms that the manner in which the scriptural message has been preserved is in itself intended by God to teach us something. That something is that God does not violate our humanity - by, for example, treating us as if we are hand-puppets, with no personal history, contexts, or points of view of our own - in order to communicate with us, just as, in orthodox Christian thought, the Incarnation did not violate the human whom God the Eternally Begotten became.

On the other hand, those through whom God spoke did not impede the divine purposes for their inspiration, just as the humanity of Jesus did not pollute the Word made flesh. We can observe, then, that incarnationalists are plenarists, of a sort. They are not, however, verbal plenarists. They do not believe God guided the word choices of the writers and editors of the Holy Scripture. They also share traits of the varied inspirationists, believing that the inspiration of the Bible is like an uneven landscape, with depth, texture and a plethora of diversity. That diversity must be considered fully when listening for God. Still, in its diversity, the Bible is one, unified, through God's inspiration of it. The whole Bible is inspired and used by God to shape us into the people God intends us to be.

The incarnationalist understands inspiration to be 'from above' - from the transcendent God - but it involves the full participation of immanent sources, which God the Spirit uses 'from below.' The texts express the humanity of their authors, including personal experience, idiosyncrasies, and contexts.

Rightly considered, contexts serve rather than inhibit the communication of meaning. While contexts do not fully determine meaning, they are vital aspects of meaning. Form cannot be separated from content any more than content can be divorced from form. As I said, humanness was not overwhelmed in this expression (or incarnation) of God's Word.

Notice that I said "God's Word" rather than "God's words." We must keep clearly in mind that the Bible is only the penultimate expression of God's speech, and that only Christ is ultimate. Only Christ was God.

We must beware of reversing the incarnational analogy. Christ is not like the Bible. While the Bible was inspired like the Word was incarnate in Christ, Christ is not like the Bible. (Reversing the analogy presses it too far.)"

(pages 62-66)

------------------

The above excerpts were taken from The Indispensable Guide to God's Word by Donald J. Brash, Ph.D. This small, 133-page book is very easy to understand as it is written for lay audiences and beginning students. Nevertheless, it is still a rigorous discourse on the nature of the Bible and hermeneutics (the field of interpreting texts). Through case studies and concise chapters (including summaries and review questions), Dr. Brash explores the foundations of interpreting texts, particularly the Bible as the Word of God. These foundations include introductory content on philosophy (epistemology and ontology), the theological concept of 'revelation', the nature of language, the historical process of the biblical canon, and much more. Having now read through The Indispensable Guide to God's Word twice, I testify that this is a little book with BIG ideas - and a great help for understanding how to read "The Book."

Friday, June 15, 2012

Tightrope Entertainment Kit

"Thousands are expected to descend on Niagara Falls tonight and millions more will watch on television as daredevil Nik Wallenda attempts an unprecedented stunt. He'll walk on a two-inch-wide tightrope some 200 feet in the air over the raging waters of Horseshoe Falls, the largest of the three falls that make up Niagara Falls." - ABC News

You can WATCH LIVE at WIVB.com (Buffalo) and also read all the FAQs about the death-defying stunt.

In the meantime, get yourself ready by checking out the incredible documentary Man on Wire from Magnolia Pictures (2008). The film recounts tightrope walker Philippe Petit's illegal walk between the Twin Towers in NYC! Watch the trailer below.

Also, get up and get movin' to Janelle Monae's funky hit (you guessed it) - Tightrope.

You can WATCH LIVE at WIVB.com (Buffalo) and also read all the FAQs about the death-defying stunt.

In the meantime, get yourself ready by checking out the incredible documentary Man on Wire from Magnolia Pictures (2008). The film recounts tightrope walker Philippe Petit's illegal walk between the Twin Towers in NYC! Watch the trailer below.

Also, get up and get movin' to Janelle Monae's funky hit (you guessed it) - Tightrope.

The "Otherworldly" Church

"We are otherworldly - ever since we hit upon the devious trick of being religious, yes even 'Christian,' at the expense of the earth. Otherworldliness affords a splendid environment in which to live. Whenever life begins to become oppressive and troublesome we just leap into the air with a bold kick and soar relieved unencumbered into so-called eternal fields. We leap over the present. We distain the earth; we are better than it. After all, besides the temporal defeats we still have our eternal victories, and they are so easily achieved. Otherworldliness also makes it easy to preach and to speak words of comfort. An otherworldly church can be certain that it will in no time win over the weaklings, all who are only too glad to be deceived and deluded, all utopianists, all disloyal children of the earth. When an explosion seems imminent, who would not be so human as to quickly mount the chariot that comes down from the skies with the promise of taking us up to a better world beyond...?

However, Christ does not will or intend this weakness; instead, he makes us strong. He does not lead us in a religious flight from this world to other worlds beyond; rather, he gives us back to the earth as its loyal children." - Dietrich Bonhoeffer, A Testament to Freedom, 89

However, Christ does not will or intend this weakness; instead, he makes us strong. He does not lead us in a religious flight from this world to other worlds beyond; rather, he gives us back to the earth as its loyal children." - Dietrich Bonhoeffer, A Testament to Freedom, 89

Thursday, June 14, 2012

Monday, June 11, 2012

Textual Healing: Why Romans 1:26-27 is Not the Text for Condemning LGBTQQ

Please read slowly and carefully. This essay deals meticulously with biblical texts and requires attention to details. As always, this important topic requires reading with an open mind and heart.

Romans 1:26-27 is one of the more frequently cited biblical texts to support the oppression and exclusion of the LGBTQQ community. But this conventional interpretation has tragically become the very antithesis to what the Apostle Paul originally intended. In its original context, Paul's words are part of a brilliantly crafted argument to expound the radical grace of the Gospel and its power to unite both Jews and Gentiles (today we should hear "Christians and non-Christians"). In the final analysis, Romans is about one thing: the power of the Gospel to generate and sustain a grace-filled community of sinners.

The words of Rom. 1:26-27 are quoted often to condemn gay persons. In doing this, however, the verses are taken out of the context of Paul's overall argument in chapters 1-3. It is therefore imperative that we understand the greater context of Paul's argument and the role that verses 26-27 play in his entire point.

The context for Paul's argument is 1:16-3:20. It all begins with Paul's proclamation that the Gospel is for both Jews and Gentiles: "It is the power of God for salvation to every one who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek," (1:16). When one reads Jew/Gentile in Paul, these two categories indicate all of humanity. With this introduction Paul lays down two essential elements of the Gospel: 1) the Gospel is universal (for everyone); and, 2) the Gospel is about fellowship (uniting Jew/Gentile).

Following this introduction Paul begins a longwinded attack on various human behaviors (1:18-32). It is here that Paul describes women and men engaging in "unnatural relations." However, what matters most is not what behaviors are being condemned, but rather who. While this passage is commonly read as if Paul is condemning all of humanity, he is not. Here Paul is speaking about the Gentiles. This is made clear by Paul's words in 19-20: "For what can be known about God is plain to them. Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely, his power and deity, have been clearly perceived in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse." (Such language would not be used to describe the Jews who knew God through God's revelation, salvation, and election)

Reading this passage as a description of the universal human condition is a common mistake. Paul is not just listing sins, he is describing the Gentiles in order to make a larger point. Verses 29-32 are not simply a list of bad behaviors, it is Paul's exaggerated condemnation of the Gentiles through a rhetorical device called a "vice list." NT scholar Craig Keener notes, "Ancient writers sometimes employed 'vice lists,' as here... Paul here sets up his readers for chapter 2," (IVP Background Commentary: New Testament, 417). It is imperative that we understand Romans 1:26-27 as part of Paul's setup for what is to come in Romans 2.

To further understand how Paul set up his argument in Romans 1:18-32 we must look at a fascinating parallel between Romans 1-3 and the Wisdom of Solomon. The Wisdom of Solomon is a deuterocanonical book that may be found in the Jewish canon, as well as many Christian Bibles. The book was popular around the same time as Paul's epistle to the Romans (First Century C.E.) and most scholars believe that Paul made intentional parallels with it. The following insights are taken from an article by Everett R. Kalin, although Keener also notes that "Paul's argument is similar to one in the Wisdom of Solomon," (Keener, 416).

In his article "Romans 1:26-27 and Homosexuality," Kalin explains that "some of the key themes and specific turns of phrase in Wisdom of Solomon 13-14 are so close to what Paul says in Rom. 1:18-32 that we might even imagine him having that text before him (mentally if not physically) as he wrote." Put simply, Paul's words in Romans sound almost identical to the words in another Jewish Scripture. To help the reader understand the parallels between Romans and Wisdom of Solomon I have created a chart. (see below, click to enlarge)

So why is this important? It is important because the two texts are almost identical in the "A" stage of their arguments, but in the "B" stage they are not. The above chart shows the "A" stage of each text's argument: the Gentiles should have known God but they did not and so they worshiped idols and God gave them up to immorality. This sets up what the authors really want to say in stage "B." The significance, however, is that Paul's "B" is unexpectedly different.

For the Wisdom text, the "B" of the argument makes clear "how differently God has treated those idolatrous Gentiles and us Jews and how different we are from them," (Kalin, 428). The main point in Wisdom's "B" is that the Gentiles are immoral and different, while the Jews are righteous and loved by God. This frame of thinking was common in the Judaism of Jesus' day; but it is not what Paul proposes in Romans 1-3.

What does Paul propose? Unity, fellowship, and the grace of the Gospel! The "B" stage in Romans is found in 2:1-3:20 and here again Kalin is helpful: "In 2:1 he turns to those who dis-approve of the Gentile's evil, in contrast to those in 1:32, who approve of it. One would think that for Paul that would be a step in the right direction; he, after all, disapproved of it too. But, on the contrary, he makes of this disapproval a judging of 'the other,' since the judge is doing the very same things.... Paul springs the trap, drops the other shoe, and offers a totally different "B": 'You too are without excuse' (anapologeitos) - the exact same word used of the Gentiles in Romans 1:20!" (Kalin, 428). I have created a figure for the "B" arguments as well.

Paul's use of the Wisdom of Solomon text is a brilliant strategy to lure the self-righteous into thinking that they are better than the immoral Gentiles. Both Jewish and Gentile Christians in Rome would have heard Paul's "A" as prototypical Jewish thinking. But while Jewish Christians probably expected a "B" like Wisdom, Paul instead offers the Gospel truth in his "B."

Imagine Jew and Gentile hearing the reality-altering truth of the Gospel: all of you are undeserving of God's grace (3:9). Only God is righteous! It is God's grace, God's love, God's gift, God's righteousness, and God's justification (3:24-26). It's not about you or your morality, it's about God.

That Paul makes the effort to craft such a clever, rhetorical trap reveals the emphasis of his argument. It is not the immoral Gentiles that he condemns, it is the self-righteous and exclusive Jews. This point is emphasized in 2:8 when Paul lambasts "those who are factious." This word ἐριθείας indicates those people who are bias toward their own social group at the expense of others. Like Jesus, Paul's major condemnation is reserved for those who think that they are in the moral majority. Paul's condemnation is for those who draw boundary lines to separate themselves from the supposedly immoral. (The irony, of course, is that this is exactly the behavior that had Jesus crucified outside of the city walls as a basphemer.)

The point of Romans 1:18-3:20 is to realize that all of humanity is united in sin. This is the true reality revealed through the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The morally exclusive communities that we attempt to construct are false realities. They are, as Margaret Alter put it, a "politic of holiness." Paul's argument in Romans 1:18-3:20 traps these groups in their self-righteousness and ideological idolatry. Both Jew and Gentile are guilty of attempting to construct their own reality through idolatry. This is what Paul means when he writes that the Jews do "the very same thing," (i.e. idolatry). But the reality of the Gospel shatters idolatry and all of our factious behavior.

What, then, does Paul offer instead of this factious behavior? After all, Romans 1-3 is just the beginning to Paul's letter and it too sets up a larger point to be made. Upon this foundation Paul proceeds to expound the power of the Gospel to generate and sustain a grace-filled community of sinners who have been saved by Christ. Kalin argues that Paul's "principle reason for the writing of Romans [is] to encourage members of various Christian congregations in Rome, divided over issues they see as vital to faith and life and worship, to welcome one another despite, and even before resolving, these differences (see Rom. 14:1-15:3 and especially 15:7)," (Kalin, 425).

Indeed, the point of Romans follows the point of the Gospel: to generate grace-filled community. But just as Paul begins his letter with an appeal to the immorality of all, I believe that we too must realize our shared brokenness in order to truly unite as a grace-filled community. Paul "sees the Gentiles as well as the Jews in the reflected light of that fire of God's wrath which is the fire of his love," (Karl Barth, A Shorter Commentary on Romans, 33). Without the realization that we are all immoral, we cannot truly grasp the extent of God's grace to everyone. Indeed this is how grace truly operates: "In our decision concerning God's revealed grace we stand or fall according to whether we allow it to be grace, God's unmerited favour towards others and towards ourselves - or not," (Barth, Romans, 34). Without realizing that "we" are just like "them," we don't get the scandal of the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the power of God's grace to create a new community and a new world.

Now, how might this translate to the contemporary church and the LGBTQQ community? First and foremost, Romans 1:26-27 must be read in the original context of Paul's argument in 1:18-3:20. The passage's main purpose is not to condemn homosexuality, it is to condemn the factious behavior of the Jews. This means that those who use 1:26-27 to distinguish themselves from those described are committing the very act that Paul condemns in this passage! Those who quote Romans 1:26-27 as evidence for excluding or persecuting LGBTQQ are living examples of the "politic of holiness" that Paul intends to eradicate. They are the "hard and impenitent... who are factious and do not obey the truth, but obey wickedness," (2:5,8).

By understanding Paul's argument we may see that Rom. 1:26-27 is not the biblical text to cite when drawing moral dividing lines concerning LGBTQQ. Instead, this text is about the power of the Gospel to move beyond factious morality to a "Gospel morality" that promotes fellowship because of God's grace to all of us immoral people.

At this point a very important clarification is necessary before the reader misunderstands my interpretation of Paul. I do no think that Paul is saying, "Never judge or condemn immoral behavior." I have, in fact, read Paul's entire letter and am aware that he encourages followers of Christ to resist sin (chap. 6-8 especially). For it seems that Paul [given what he could know about human beings at his time] disapproved of the Gentile vices in 1:18-32. However, I believe that Paul is saying, "Do not exclude these brothers and sisters from your community. Why? Because you are just as immoral and because the grace of God is immeasurable." This interpretation fits the overall purpose of Romans.

Here also I shall take the opportunity to respond in advance to a likely refutation. In the spirit of my interpretation of Paul, the reader may ask, "Where, then, do we draw the line? Are we to welcome any/all behavior in our community in the name of grace?" This is an excellent question and the answer, I believe, is complicated. We must remember that grace does not jettison morality; nor the responsibility that it requires. I believe that both Jesus and Paul reveal a Christian morality whose primary goal is to generate and sustain a grace-filled community. This means that not all behavior is appropriate for Christian community. Murder, deceit, and verbal abuse, for example, are anti-community behaviors. They do not fulfill the Law as both Jesus and Paul taught to love your neighbor as yourself (Mk 12:31; Rom. 13:9). Such behaviors are immoral because they destroy community and the Gospel is ultimately about building community. As such, they are undesirable for Christian community and should be managed with love according to the appropriate context. It should be noted that to compare homosexuality to anti-communal behavior like murder is not only absurd, but tragically disrespectful. If one cannot see the colossal difference between one who kills and one who loves, then there is no hope for establishing a Christian morality at all.

At the same time, however, the Gospel reveals that morality alone is not enough. Relying only upon a set of rules or doctrinal guidelines will always fail because we are all immoral. Morality by itself inevitably leads to the factious politics of holiness and the exclusion of others. But this is the antithesis of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Genuine human fellowship is made possible by the grace of the Gospel. Only grace makes possible the fellowship of sinners.

This, as I have shown, is the real argument of Paul found in Romans 1:18-3:20. Rather than a moralized diatribe against homosexuality, 1:26-27 is part of a jarring polemic against a sociological pattern that is far too common among religious communities. If we are to hear Paul today, we must ask ourselves which "B" argument we identify with. When it comes to issues concerning LGBTQQ, do we sound like those in Wisdom of Solomon: the self-righteous moral majority? Or are we more like Paul's description: without excuse, just like them, doing the very same things? As Karl Barth suggested, the Gospel of grace stands or falls on our ability to answer this question. Our answer determines whether or not we allow God's unmerited favor toward others and ourselves - or not.

Christians who refer to this text in an effort to condemn LGBTQQ behavior no doubt take the Bible very seriously. But so do I. And I believe that taking this text seriously means reading it in its original context, both historical and literary. My hope is that this kind of reading might lead Christians to a kind of "textual healing" - a restoration of the text to a more faithful interpretation of Paul's letter. More importantly, I hope that the restoration of the text might also lead to the healing of our communities. It seems that this too was Paul's hope and his reason for proclaiming the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Christians in Rome nearly 2,000 years ago.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)