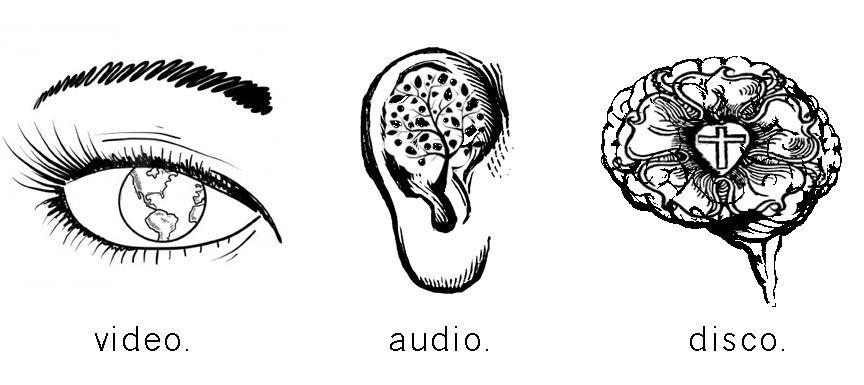

Are you afraid of postmodernism? Well do not fear, James Smith is here. In his book Who's Afraid of Postmodernism? Taking Derrida, Lyotard, and Foucault to Church James K. A. Smith presents a clear, concise introduction to postmodern philosophies and their ramifications for the Christian church. This is the best book on postmodernism/church that I have encountered.

This short work consists of five chapters, the last being the most substantive. Hence, I will devote the most space to it. Smith introduces each chapter with a film that illustrates major points regarding the chapter's content. I found his exposition of films both entertaining and beneficial for grasping various concepts (not to mention it made me want to watch Whale Rider again - great film). In the three middle chapters Smith dialogues with one of the three philosophers, providing good primary source quotations.

After a broad introductory chapter Smith delves into Derrida's claim, "There is nothing outside the text." Here Smith's goal is to unpack the "bumper-sticker" interpretation of Derrida's quote and better understand what exactly the Frenchman meant. Smith explains that Derrida essentially meant that "everything is interpretation" (42). Smith argues that this liberates Christians from having to prove Christian claims to be universally known by all people, at all times, in all places (48). Instead, the church may embrace a confessional theology in which the interpreting community determines meaning (53, see review of last chapter below).

In chapter three Smith corrects a bumper-sticker understanding of Lyotard's claim that postmodernism is the rejection of metanarratives. This claim seems to oppose the very nature of the church whose theology claims a creator God guiding the cosmos to a telos. However, this is not, in fact, what Lyotard meant. Rather, Smith explains Lyotard's definitiion of metanarrative as "universal discourses of legitmation that mask their own particularly; that is, metanarratives deny their narrative ground even as they proceeed on it as a basis," (69). Examples: modern scientific knowledge, Darwinism, capitalism. Thus, the narrative of Scripture, which does not attempt to legitimate itself "by an appeal to universal, autonomous reason but rather by an appeal to faith (or, to translate, myth or narrative)" is not considered a metanarrative by Lyotard's - or postmodernism's - standards (68). Smith correctly notes a beautiful ramification for the church: narrative does not attempt to prove its claims, but rather proclaims them within a story.

Smith's last philosophical sparring partner is Michael Foucault (chapter four). Again Smith attempts to situate a bumper-sticker understanding of Foucault. Here he tackles Foucault's claim that "power is knowledge." Essentially, Foucault's philosophy provides a comprehensive description of modern disciplinary systems (tracking from 18th century to modern day). In the end Smith understands Foucault to assert that "social institutions and relationships are necessarily constructed on the basis of power relations," (100). Smith paints Foucault as a "closeted Enlightenment thinker" (97) because he is so often understood as a "protest thinker" who champions the rights of the individual. As for the church, Smith would like to see the church reject the modernist notion of the autonomous individual and embrace the disciplinary form of the gospel (viz. Christ's Lordship). For me, this was the most difficult chapter because Foucault's philosophy is quite dense. But the concept of discipline is something that anyone who claims to be a disciple ought to explore.

In the last chapter titled "Applied Radical Orthodoxy" Smith offers a number of substantive thoughts in response (too much to cover here). Smith rightly argues postmodernism allows for "a robust confessional theology and ecclesiology that unapologetically reclaims premodern practices in and for a postmodern culture," (116). What I appreciate the most in this chapter is Smith's recovery of premodern epistemology. I think that this is truly the area where postmodernism offers the church a way out of modernity's epistemic prison and back into the movement of confessing Christ.

Specifically, Smith shrewdly points out that many postmoderns, including Derrida and Caputo, ironically endorse a Cartesian (modern) epistemology when they claim that we cannot know, we can only believe. The irony is that such a view equates knowledge with indubitable certainty (omniscience); faith is therefore located in opposition to knowledge (a Cartesian and Enlightenment definition). We cannot say we know things about God with certainty, we can only believe. What results is a "religion without religion" (119).

But what Derrida and Lyotard (see also Thomas Khun, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions) have shown is that all knowledge is uncertain and depends upon a degree of faith. Smith refers to pre-Cartesian epistemology that correctly distinguished between comprehending God and knowing God. The postmodern church may relinquish claims of absolute knowledge without giving up knowing altogether.

Ultimately Smith contends for a "logic of incarnation" (122) that allows the Christian church to resist the "modern notion of an ahistorical, a-geographical, transcendental religion." Instead, the Christian church may affirm and embody a particular, finite narrative; one that confesses that "God became flesh at a particular time ("under Pontius Pilate") and in a particular place ("born of the Virgin Mary")," (122).

This, I believe, frees the Christian church from the epistemic idols of modernity and allows us to once again embrace a confessional theology. And, ultimately, Smith's "Radical Orthodoxy" offers a solid middle ground between modern and postmodern extremes.

My only reservation about Smith's "Radical Orthodoxy" is the primacy he gives to specific revelation. I agree with him that God's revelation in Christ and Scripture should act as the governing revelation for the Christian community (126), but Smith offers no concrete suggestions as to what this might look like. My issue is that it is precisely the interpreting community (historical and contemporary) who makes sense of Gods' revelation in Christ and Scripture. What, then, is the role of the community? I imagine that Smith expands on this in his Introducing Radical Orthodoxy: Mapping a Post-secular Theology (2004).

As I've said throughout, this book is a fantastic introductory read. It is easy to read, entertaining, and provides a substantial amount of primary source quotations that allowed me to "get to know" Derrida, Lyotard, and Foucault a bit. Whether or not you're just starting out in studies of postmodernism or you've been exploring for years, this book is a worthwhile read.