So I just finished reading Peter Rollins' book Insurrection and I feel enthusiastic and somewhat intoxicated by life. I'm not sure if Rollins would be happy about this or not. Much of his book is an explicit condemnation of the kind of Christianity that attempts to make us feel happy and content (more on this below). But, at the same time, Rollins offers an invigorating appeal to truly participate in the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ so that we might come to know God in the dynamics of life itself. This is why I've walked away feeling hopeful about my existence in this mystery we call life.

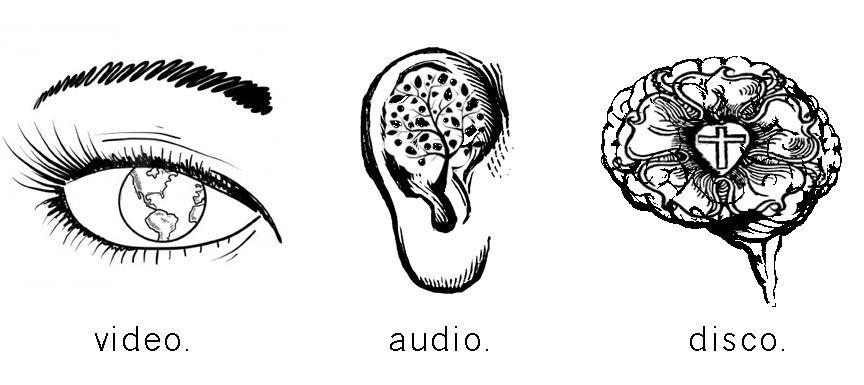

Rollins prefaces his work by explaining his approach; a method he calls "pyro-theology." It is the attempt to "burn our sacred temples in order to discover what, if anything, remains," (xv). Like any good thinker, Rollins wants to deconstruct our presuppositions. What is particularly astute in his preface is his notion that the Church must stop trying to "go back" to some desirable time period when the Church was a certain way. We must quit attempting to go back to the time before the Church was distorted by Constantine. We must quit attempting to go back to theology before Neo-Platonism or even before Paul. These attempts, Rollins argues, "fail to go back far enough," (xiii, italics original). Instead, Rollins asserts that Christians today must return "to the event that gave birth to the early Church," (xiii, italics original). This observation is an invitation to experience afresh the Christ Event. Hence, Rollins work focuses on the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ.

The first half attends to Crucifixion. For Rollins, the Crucifixion of Christ is paradigmatic for the death of the "God of religion." Here he borrows heavily from Dietrich Bonhoeffer's work on the "death of God," especially what Bonhoeffer called the deus ex machina - the God out of the machine. This "God of religion" is the kind of God that serves as a psychological crutch. It is the God that serves a part in the narrative of life just to fill in the gaps or to serve a pragmatic function. This God is the nice, pre-packaged God that grounds our life in something predictable and certain. It is the God that says, "Everything will be OK."

But what is worse, argues Rollins, is that the Christian Church has twisted the Crucifixion of Christ into this same kind of God. Instead of taking seriously the words of Christ on the Cross - "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" - the Church "seems dedicated to reducing the Crucifixion to mere mythology," (21). What Rollins means is that the Church has robbed the Crucifixion of its sting and turned it into a myth that "brings meaning, order, and stability to our fragmented experience. ... When the Crucifixion is understood as offering the security of meaning, rather than being the site where meaning is ripped away, then any experience of doubt, unknowing, and loss that is found there is eclipsed by an even greater certainty and everything is really fine." (22).

More than just an experience of doubt and loss, the Crucifixion is the very death of the God of religion. In the Crucifixion Jesus experiences the fundamental loss of the God of certainty and comfort. The deus ex machina is dead. But even more than this, the Crucifixion reveals that doubt, loss, and uncertainty are fundamental means into the presence of God. Rollins explains, "Radical doubt, suffering, and the sense of forsakenness are central aspects of Christ's experience and thus a central part of what it means to participate in Christ's death," (29, italics original).

Now we understand the subtitle, "To believe is human. To doubt, divine." Rollins' thoughts reminded me of Jurgen Moltmann's book The Crucified God in which Moltmann writes, "To know God in the cross of Christ is a crucifying form of knowledge, because it shatters everything to which a man can hold and on which he can build, both his works and his knowledge of reality, and precisely in so doing sets him free," (212).

One of Rollins' strengths is that he is a trained psycho-analyst (very influenced by Jacque Lacan) and offers very insightful observations about human behavior. Rollins devotes much of the Crucifixion section to analyzing how Christians avoid the truth of the Crucifixion. To save space I shall just list a few of examples.

1. We care more about the beliefs of others than our own and so refuse to embrace doubt (i.e. the view we hold of how others perceive us holds the most power in our lives). [pp. 42-46]

2. The Church provides a safety blanket (i.e. provides comfort so we can "doubt" while not truly experiencing doubt, horror, loss, etc.) [pp.47-49]

3. The pastor (or leaders) believe for us (i.e. as long as someone else doesn't doubt this thing I'm doubting, I'll hang on) [pp. 50-52]

Rollins rightly observes that, "Existential crisis arises not because of some new information that a person receives, but because they are now confronted with what they already know but refuse to admit," (67). From here through the end of the section on Crucifixion, Rollins sustains a polemic against escapism in its many forms. Ultimately, the God of religion is a form of escaping the truth of the world. But the Crucifixion invites us to experience the world as it truly is: to stare into the void of nothingness, meaningless, emptiness... and to feel it stare back. This is what it means to participate in the Crucifixion with Christ (Romans 6).

What then shall we say? That life is meaningless and hollow? No. But we will never discover the meaning of our existence if we refuse to face up to the realities that "life is finite, our activities are meaningless, and our lives are more dark and selfish than the image we have of ourselves. [And] we avoid each of these through various distractions, a religious notion of God, and carefully crafted false stories of who we are," (106-107). Only when we have gone through Crucifixion are we ready for Resurrection.

And what is Resurrection? For Rollins it is not simply an answer to the Cross in order to re-establish order. Instead, it is "the state of being in which one is able to embrace the cold embrace of the Cross. If the Crucifixion marks the moment of darkness, then the Resurrection is the very act of living fully into the darkness and saying 'Yes' to it," (112).

The Resurrection is all about Eternal Life: a kind of life that transforms the way we live here and now. Eternal Life does not rid us from suffering and darkness, but it allows us to embrace them with the Love of the Cross. And when this happens we literally rob these dark places of their sting. The Apostle Paul wrote of the Resurrection life: "Where O death is your victory? Where O death is your sting?" (1 Cor. 15: 55).

What fundamentally changes for Rollins is how we know God. Rollins makes clear that we cannot know God without going through Crucifixion or Resurrection. Only in the Resurrection life do we then discover that "God is present in the very act of love itself," (118). Rollins explains that God ceases to be a Being or a Something "out there" that we attempt to relate to in special moments or in ritualist acts. Instead, "God is that which transforms how we experience everything, i.e. love," (123, italics original). Now you may begin to understand why this book left me with excitement for life.

In the rest of the section on Resurrection Rollins offers a compelling look into the life of Mother Theresa as an example of what it means to live into Crucifixion and Resurrection. There is not room to expound on this, but if you have any knowledge of Mother Theresa then you know that she experienced profound darkness for years and yet embraced it with the Love of God. This book is worth picking up just to read about Mother Theresa.

In addition, Rollins presents some great ideas for creating communities that embrace Crucifixion and live out Resurrection (including some songs and poems). And in his conclusion he emphasizes the fact that participating in Christ's Crucifixion and Resurrection means enacting them in our daily lives.

The 180-book is a quick and enjoyable read. Pete offers tons of humorous illustrations and draws some ingenious analogies from movies and TV. He writes a lot like he speaks: fast, passionate, and chaotic. My only real criticism is that Rollins does not delve deeper into the theological implications of some of his thinking (e.g. I want to know his thoughts on the Trinity). But I think that he remains ambiguous on purpose in many areas. Nevertheless, this is a book with a lot of valuable ideas. And it is a welcomed conversation partner for anyone trying to figure out what it means to follow the Crucified Messiah.